INSIGHT

Alternative Investment Series – Part 1: What You Should Know

Daniel Figueredo • March 3, 2021

Industries: Blockchain & Digital Assets

Whether you are the head of a nonprofit or foundation with an endowment, an institutional investor, or a high-net worth individual, you are probably continuing to seek new and creative ways to better diversify your investment portfolios, increase returns and reduce risk.

Many are rethinking their asset allocations beyond traditional asset classes, such as a balanced allocation of 60% to stocks and 40% to bonds and fixed income. Alternative investments are becoming more prevalent in the mix of investment portfolios and asset allocation.

The term “alternative investments” is often loosely used, but generally refers to other categories of investments than traditional classes, such as stocks and bonds. Alternative investments often come in the form of investment funds, which are either private funds or publicly traded and subject to the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the “1940 Act”).

This article and series will focus primarily on private investment funds, such as:

- Venture capital funds

- Hedge funds

- Private equity funds

- Real estate funds

- Cryptocurrency funds

- Fund of funds

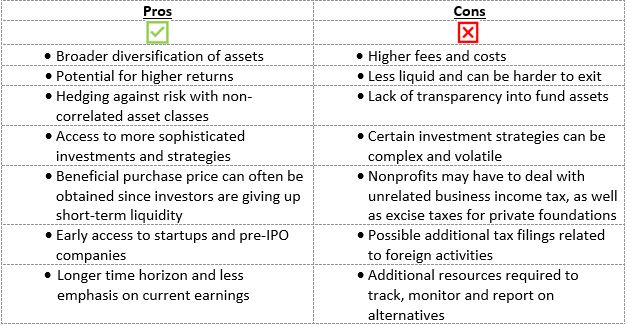

Every investor looking to allocate a portion of their portfolio to alternatives should certainly conduct their own due diligence and weigh the pros and cons, some of which are described below and will vary in emphasis depending on the type of fund, strategy and terms. Alternative investment funds come in all sizes as well, from a few million dollars to billions of dollars.

The size of fund and experience of its fund managers are also important considerations before jumping in. The benefits of alternative investments, some of which are listed below, are well worth the consideration by investors. But institutions and individuals should not enter into the world of alternative investing blind. Being well-informed is critical to making confident investment decisions.

Private Fund Exemptions from the 1940 Act

Private investment funds benefit from certain exemptions of the 1940 Act if they meet the criteria found primarily in Sections 3(c)(1) or 3(c)(7). An exemption from the 1940 Act allows the fund to avoid certain Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) registration, public filing, ongoing disclosure, and other requirements.

The 3(c)(1) exemption includes limiting the fund to no more than 100 “accredited investors,” while the 3(c)(7) exemption requires investors to be “qualified purchasers.” Additionally, the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 effectively limits the number of investors in a 3(c)(7) exempt fund to below 2,000.

Accredited Investors

The criteria for being an “accredited investor” has historically been based on financial thresholds of annual income and net worth.

The criteria for individuals are:

- Net worth (along with his/her/their spouse) that exceeds $1,000,000 (excluding the value of his/her/their primary residence); or

- Income in excess of $200,000 (or joint income in excess of $300,000 with spouse) in each of the two most recent years with a reasonable expectation of reaching the same income level in the current year.

The criteria for business entities are:

- Owned exclusively by accredited investors; or

- Is not formed for the special purpose of acquiring the interest in the fund and has total assets in excess of $5,000,000.

(A recent update: The SEC recently published a final rule on Oct. 9, 2020 updating the definition of “accredited investor”, which went into effect on Dec. 8, 2020. The updates to the definition are an acknowledgment by the SEC that participation in the private equity markets should not be exclusively determined based on financial tests. The amendments to the definition of “accredited investor” in Rule 501(a) of Regulation D created additional categories of qualifying individuals and entities, as well as other modifications.)

Additional Categories and Modifications

For individuals:

- For purposes of calculating joint net worth and joint income as described above, the SEC now allows for the inclusion of spousal equivalents, defined as a cohabitant occupying a relationship generally equivalent to that of a spouse.

- Individuals with one or more professional certifications or designations or credentials from an accredited educational institution designated as qualifying by the SEC (e.g. Series 7, Series 82, Series 65) and are in good standing; or

- Individuals who are knowledgeable employees of a private fund, where knowledgeable employee has the same definition as Rule 3c-5(a)(4) of the 1940 Act.

For business entities:

- The $5,000,000 threshold above now includes several types of entities to the list, such as SEC-registered and state-registered investment advisers, exempt reporting advisors, rural business investment companies, and limited liability companies; or

- Family offices and their family clients, as defined in Rule 202(a)(11)(G)-1 or the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

Qualified Purchasers

A “qualified purchaser” is an investor who meets any of the following criteria:

- An individual or family-owned business not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the interest in the fund that owns $5,000,000 or more in investments; or

- A trust not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the interest in the fund that is sponsored by and managed by qualified purchasers; or

- An individual or entity not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the interest in the fund that owns and invests at least $25,000,000 in investments (or someone who is acting on account of such person); or

- An entity of which each beneficial owner is a qualified purchaser.

Common Strategies for Alternatives

Types of private alternative investment funds that are attracting attention from the nonprofit community are hedge funds and private equity:

- Hedge funds: Hedge funds employ a number of different strategies, often designed to be non-correlated to movements in traditional asset classes or the overall market. They also have more trading flexibility to execute their profit-making strategy, and can conduct short selling of stock (betting on a decline in value), leveraging and margin trading (borrow money to make big bets), and trade derivatives (such as stock options, futures, and forward contracts). They may follow an event-driven approach (take advantage of a corporate news or events, distress in the market, etc.), a relative value arbitrage approach (exploit temporary price disparities between related securities), or a directional approach to trade both the ups and downs of the market (look for overvalued stocks and bet against them).

- Venture capital funds: Venture capital funds invest in early-stage startups and emerging growth companies. They aim to get in early on a novel idea and help it grow before exiting through an initial public offering, a merger or acquisition, or another strategy.

- Cryptocurrency funds: These funds follow many of the same strategies as hedge funds or venture capital funds, but invest primarily in digital assets and hold little fiat currency (i.e., cash). Because of the emphasis on digital assets, the decentralization of markets, and uncertain regulatory environment, these funds have many additional considerations and opportunities that come into play that puts them in a category of their own.

- Private equity funds: Investors provide capital, with the goal of investing in private companies to grow value and profits. PE funds often aim to take a controlling stake in their portfolio companies. Strategies can include leveraged buyouts (using debt to finance the acquisition of a company), growth capital (a minority investment in a mature company looking for capital to expand, enter new markets or acquire another business), turnarounds (helping declining companies in distress), or many forms of lending and credit (direct lending, mezzanine debt, distressed debt).

- Real estate funds: These funds can execute a number of different strategies and specialty focus by asset class. Real estate funds often have an income-generating component from properties in the portfolio. Some strategies might include real estate development, joint ventures, special opportunity funds, and structured finance.

- Other real assets funds: These types of funds can invest in many other types of real assets, such as, oil and gas, precious metals, commodities, art collections and other collectibles, royalty income, etc.

Open-End vs. Closed-End Funds

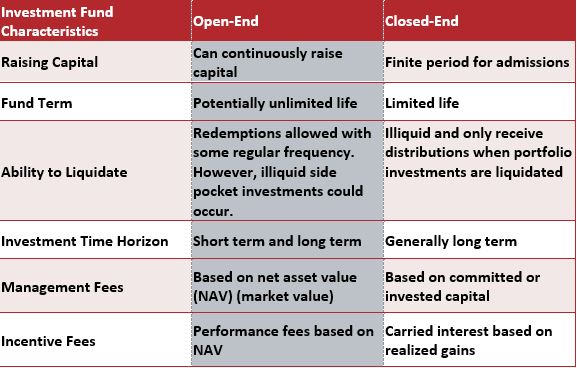

Understanding the legal structure of the alternative fund you are interested in is also essential for making a sound decision. Alternative investments come with different degrees of liquidity (the ease and speed with which an asset can be converted into cash) and operate on different time scales, two factors which should be assessed for overall fit.

Alternative funds can be either open-end or closed-end. Open-end funds are more liquid and require less time to redeem your interests if you need funds, therefore they often need to keep enough liquid assets on hand for potential redemptions. Closed-end funds, by comparison, have a finite period in which they accept admissions into the fund, exist only for a limited amount of time, and typically do not allow redemptions and only distribute proceeds from liquidated portfolio investments. As such, they also generally do not maintain significant amounts of cash and liquid assets.

Open-end fund structures are often used for hedge funds, which play well with their investment strategies, while closed-end funds are often utilized by VC funds, PE funds and real estate funds. Cryptocurrency funds tend to be close to evenly split between those set up as open-end vs. closed-end. Certain jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands, have these concepts embedded into their laws. We commonly think of the Cayman Islands Private Funds Law as pertaining to closed-end funds, while the Mutual Funds Law pertains to open-end funds (see BPM’s recent article on requirements for Cayman Island funds).

Both types of funds typically earn management fee (often around 2%) and incentive or performance-based fees (often around 20%). Management fees are most commonly assessed based on the amount of capital committed, capital contributed, or net asset value of the fund. The fund manager also receives a share of the profits associated with any realized gains. The incentive or performance-based fees are earned as a percentage of the gains achieved for investors. Many funds will have thresholds or high-water marks that need to be achieved first to ensure fund managers do not get paid on poor performance.

Below is a summary of some key attributes and differences between open-end and closed-end funds:

Summary

Private alternative investments are increasing in appeal and the SEC has worked to expand the universe of potential investors qualified to participate in them. By understanding a fund’s strategy and structure, you will be better enabled to determine how the potential investment fits into your overall asset allocation, what kind of risks you are taking or reducing, and how long you may have to wait for your payoff. In Part 2 of our series, we will cover more in depth some basic terminology and what to pay attention to in your partnership agreements and offering documents.

For more than three decades, BPM has dedicated itself to providing solutions for the unique operational and financial challenges faced by businesses and nonprofit organizations. To learn more, contact BPM Partner Daniel Figueredo.

Daniel Figueredo

Partner, Advisory and Assurance

Nonprofit Co-leader

FinTech Leader

Daniel is an Advisory and Assurance Partner at BPM, and a leader in BPM’s Nonprofit, Blockchain and Digital Assets and …

Start the conversation

Looking for a team who understands where you’re headed and how to help you get there? Whether you’re building something new, managing growth or preserving success, let’s talk.